Bread is an extremely ambiguous concept. The name of a table product made of flour can be synonymous with the word "life", sometimes it is equivalent to the concept of "income", or even "salary". Even purely geographically, bread can be called products that are very far from each other.

The history of bread goes back thousands of years, although the introduction of peoples to this most important nation was gradual. Somewhere baked bread was eaten thousands of years ago, and the Scots defeated the English army back in the 17th century simply because they were full - they baked their own oat cakes on hot stones, and English gentlemen died of hunger, waiting for the delivery of baked bread.

A special attitude to bread in Russia, which was rarely well-fed. Its essence is the saying "There will be bread and a song!" There will be bread, the Russians will get everything else. There will be no bread - victims, as the cases of famine and the blockade of Leningrad show, can be counted in millions.

Fortunately, in recent years bread, with the exception of the poorest countries, has ceased to be an indicator of well-being. Bread is now interesting not for its presence, but for its variety, quality, variety and even its history.

- Bread museums are very popular and exist in many countries of the world. Usually they display exhibits illustrating the development of bakery in the region. There are also curiosities. In particular, M. Veren, the owner of his own private museum of bread in Zurich, Switzerland, claimed that one of the flatbreads displayed in his museum is 6,000 years old. How the date of production of this truly eternal bread was determined is not clear. Equally unclear is the way in which a piece of flatbread in the New York Bread Museum was given the age of 3,400 years.

- Per capita consumption of bread by country is usually calculated using various indirect indicators and is approximate. The most reliable statistics cover a wider range of goods - bread, bakery and pasta. According to these statistics, Italy is in the lead among developed countries - 129 kg per person per year. Russia, with an indicator of 118 kg, ranks second, ahead of the United States (112 kg), Poland (106) and Germany (103).

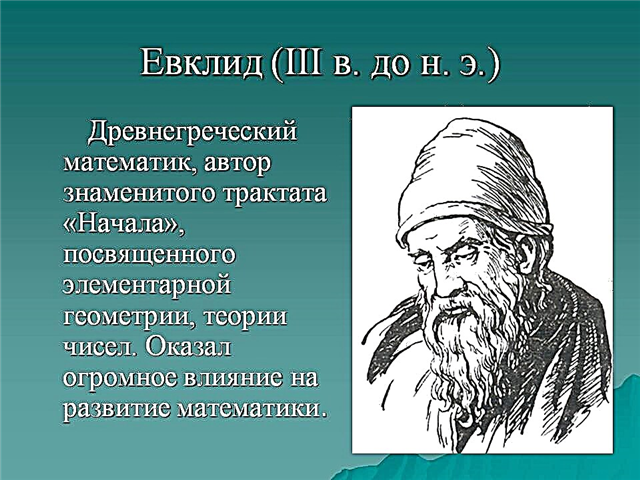

- Already in Ancient Egypt, there was a developed complex culture of bakery. Egyptian bakers produced up to 50 types of various bakery products, differing not only in shape or size, but also in the dough recipe, filling and preparation method. Apparently, the first special ovens for bread also appeared in Ancient Egypt. Archaeologists have found many images of ovens in two compartments. The lower half served as a firebox, in the upper part, when the walls were well and evenly warmed up, bread was baked. The Egyptians did not eat unleavened cakes, but bread, similar to ours, for which the dough undergoes a fermentation process. The famous historian Herodotus wrote about this. He blamed the southern barbarians that all civilized peoples protect food from decay, and the Egyptians specifically let the dough rot. I wonder how Herodotus himself felt about the rotten juice of grapes, that is, wine?

- In the era of antiquity, the use of baked bread in food was a completely clear marker that separated civilized (according to the ancient Greeks and Romans) people from barbarians. If the young Greeks took an oath in which it was mentioned that the borders of Attica were marked with wheat, then the Germanic tribes, even growing grain, did not bake bread, content with barley cakes and cereals. Of course, the Germans also considered the southern sissy bread-eaters to be inferior peoples.

- In the 19th century, during the next reconstruction of Rome, an impressive tomb was found right inside the gate on Porta Maggiore. The magnificent inscription on it said that in the tomb rests Mark Virgil Euryzac, a baker and supplier. A bas-relief found nearby testified that the baker was resting next to his wife's ashes. Her ashes are placed in an urn made in the form of a bread basket. On the upper part of the tomb, the drawings depict the process of making bread, the middle one looks like the then grain storage, and the holes in the very bottom are like dough mixers. The unusual combination of the baker's names indicates that he was a Greek named Evrysak, moreover, a poor man or even a slave. However, due to labor and talent, he not only managed to get rich so much that he built himself a large tomb in the center of Rome, but also added two more to his name. This is how social elevators worked in republican Rome.

- On February 17, the ancient Romans celebrated Fornakalia, praising Fornax, the goddess of furnaces. The bakers did not work that day. They decorated bakeries and ovens, distributed free baked goods, and offered prayers for a new harvest. It was worth praying - by the end of February the grain reserves of the previous harvest were gradually running out.

- "Meal'n'Real!" - yelled, as you know, the Roman plebs in case of the slightest dissatisfaction. And then, and the other rabble, flocking to Rome from all over Italy, received regularly. But if the spectacles did not cost the budget of the republic, and then the empire, practically nothing - in comparison with the general expenses, then the situation with bread was different. At the peak of the free distribution, 360,000 people received their 5 modiyas (about 35 kg) of grain per month. Sometimes it was possible to reduce this figure for a short while, but still tens of thousands of citizens received free bread. It was only necessary to have citizenship and not be a horseman or patrician. The size of the grain distributions well illustrate the wealth of ancient Rome.

- In medieval Europe, bread was used as a dish for a long time even by the nobility. A loaf of bread was cut in half, the crumb was taken out and two bowls for the soup were obtained. Meat and other solid foods were simply placed on slices of bread. Plates as individual utensils replaced bread only in the 15th century.

- Since about the 11th century in Western Europe, the use of white and black bread has become a property divider. Landowners preferred to take tax or rent from peasants with wheat, some of which they sold, and some of which they baked white bread. Wealthy citizens could also afford to buy wheat and eat white bread. The peasants, even if they had wheat left after all the taxes, preferred to sell it, and they themselves managed with fodder grain or other cereals. The famous preacher Umberto di Romano, in one of his popular sermons, described a peasant who wants to become a monk just to eat white bread.

- The worst bread in the part of Europe adjacent to France was considered Dutch. The French peasants, who themselves ate not the best bread, considered it generally inedible. The Dutch baked bread from mixtures of rye, barley, buckwheat, oat flour and also mixed beans into the flour. The bread ended up being earthy black, dense, viscous and sticky. The Dutch, however, found it quite acceptable. White wheat bread in Holland was a delicacy like a pastry or cake, it was eaten only on holidays and sometimes on Sundays.

- Our addiction to “dark” breads is historical. Wheat for Russian latitudes is a relatively new plant; it appeared here around the 5th-6th centuries AD. e. Rye had been cultivated for thousands of years by that time. More precisely, it will even say that it was not grown, but harvested, so unpretentious rye. The Romans generally considered rye a weed. Of course, wheat gives much higher yields, but it is not suitable for the Russian climate. The mass cultivation of wheat began only with the development of commercial agriculture in the Volga region and the annexation of the Black Sea lands. Since then, the share of rye in crop production has been steadily decreasing. However, this is a worldwide trend - rye production is steadily decreasing everywhere.

- Alas, you cannot erase the words from the song. If the first Soviet cosmonauts were proud of their food rations, which were practically indistinguishable from fresh products, then in the 1990s, judging by the reports of the crews who visited orbit, the ground services that provided food worked as if they expected to receive tips even before the crews started. The astronauts could well come to terms with the fact that the labels with the names were confused on the packed dishes, but when bread ran out after two weeks of a many-month flight on the International Space Station, this caused natural indignation. To the credit of the flight management, this nutritional imbalance was promptly eliminated.

- The story of Vladimir Gilyarovsky about the appearance of buns with raisins in the baker Filippov's is widely known. They say that in the morning the governor-general found a cockroach in the sieve bread from Filippov and summoned the baker for proceedings. He, not bewildered, called the cockroach a raisin, bit off a piece with an insect and swallowed it. Returning to the bakery, Filippov immediately poured all the raisins into the dough. Judging by Gilyarovsky's tone, there is nothing extraordinary in this case, and he is absolutely right. A competitor, Filippov Savostyanov, who also had the title of supplier to the yard, had feces in the well water on which baked goods were prepared more than once. According to an old Moscow tradition, bakers spent the night at work. That is, they swept the flour off the table, spread the mattresses, hung the onuchi over the stove, and you can rest. And despite all this, Moscow pastries were considered the most delicious in Russia.

- Until about the middle of the 18th century, salt was not used at all in baking - it was too expensive to wastefully add to such an everyday product. It is now generally accepted that bread flour should contain 1.8-2% salt. It shouldn't be tasted - the addition of salt enhances the aroma and flavor of the other ingredients. In addition, salt strengthens the structure of the gluten and the whole dough.

- The word "baker" is associated with a cheerful, good-natured, plump man. However, not all bakers are benefactors of the human race. One of the famous French manufacturers of bakery equipment was born into a family of bakers. Immediately after the war, his parents bought a bakery in the suburbs of Paris from a very wealthy woman, which was then a rarity for the owner of the bakery. The secret of wealth was simple. During the war years, French bakers continued to sell bread on credit, receiving money from buyers at the end of the agreed period. Such trade during the war years, of course, was a direct road to ruin - there was too little money in circulation in the occupied part of France. Our heroine agreed to trade only on the terms of immediate payment and began to accept prepayment in jewelry. The money earned during the war years was enough for her to buy a house in a fashionable area of Paris. She did not put the decent remainder in the bank, but hid it in the basement. It was on the stairs to this basement that she ended her days. Descending once again to check the safety of the treasure, she fell and broke her neck. Perhaps there is no moral in this story about unrighteous profit on bread ...

- Many have seen, either in museums or in pictures, the notorious 125 grams of bread - the smallest ration that employees, dependents and children received during the worst period of the blockade of Leningrad during the Great Patriotic War. But in the history of mankind there were places and times when people received about the same amount of bread without any blockade. In England, workhouses in the 19th century gave out 6 ounces of bread a day per person - just over 180 grams. Workhouse residents had to work under the overseers' sticks 12-16 hours a day. At the same time, workhouses were formally voluntary - people went to them so as not to be punished for vagrancy.

- There is an opinion (strongly, however, simplified) that the French king Louis XVI led such a wasteful lifestyle that, in the end, the whole of France got tired of, the Great French Revolution happened, and the king was overthrown and executed. The costs were high, only they went to the maintenance of the huge yard. At the same time, Louis' personal spending was very modest. For years he kept special account books in which he entered all expenses. Among others, there you can find records like “for bread without crusts and bread for soup (already mentioned bread plates) - 1 livre 12 centimes”. At the same time, the staff of the court had a Bakery Service, which consisted of bakers, 12 baker's assistants and 4 pastries.

- The notorious “crunching of a French roll” was heard in pre-revolutionary Russia not only in rich restaurants and aristocratic drawing rooms. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Society for the Guardianship of Popular Sobriety opened many taverns and teahouses in provincial cities. The tavern would now be called a canteen, and the teahouse - a cafe. They did not shine with a variety of dishes, but they took the cheapness of bread. The bread was of a very high quality. Rye cost 2 kopecks per pound (almost 0.5 kg), white of the same weight was 3 kopecks, sieve - from 4, depending on the filling. In the tavern, one could buy a huge plate of rich soup for 5 kopecks, in the teahouse, for 4 - 5 kopecks, drink a couple of tea, having ate it with a French bun - a hit on the local menu. The name "steam" appeared because two lumps of sugar were served to a small teapot of tea and a large boiling water. The cheapness of taverns and teahouses is characterized by a mandatory poster above the cash register: “Please do not bother the cashier with the exchange of big money”.

- Tea houses and taverns were opened in large cities. In rural Russia, there was a real trouble with bread. Even if we take out the regular cases of famine, in relatively productive years, the peasants did not eat enough bread. The idea to evict the kulaks somewhere in Siberia is not at all the know-how of Joseph Stalin. This idea belongs to the populist Ivanov-Razumnov. He read about the ugly scene: bread was brought to Zaraysk, and the buyers agreed not to pay more than 17 kopecks per pood. This price actually doomed peasant families to death, and dozens of farmers were lying in vain at the feet of the kulaks - they did not add a dime. And Leo Tolstoy enlightened the educated public, explaining that bread with quinoa is not a sign of disaster, disaster is when there is nothing to mix with the quinoa. And at the same time, in order to promptly export grain for export, special branch narrow-gauge railways were built in the grain-growing provinces of the Chernozem region.

- In Japan, bread was not known until the 1850s. Commodore Matthew Perry, who pushed the establishment of diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States with the help of military steamers, was invited by the Japanese to a gala feast. Having looked around the table and tasted the best dishes of Japanese cuisine, the Americans decided that they were being bullied. Only the skill of the translators saved them from trouble - the guests nevertheless believed that they were really masterpieces of local cuisine, and a crazy sum of 2,000 gold was spent for lunch. The Americans sent for food on their ships, and so the Japanese saw baked bread for the first time. Before that, they knew dough, but they made it from rice flour, eaten raw, boiled, or in traditional cakes. At first, bread was voluntarily and compulsorily consumed by Japanese school and military personnel, and only after the end of World War II, bread entered the daily diet. Although the Japanese consume it in much smaller quantities than Europeans or Americans.