If the history of Russia was written by techies, and not by the humanities, then “our all” would have been, with all due respect to him, not Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, but Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834 - 1907). The greatest Russian scientist is on a par with the world's luminaries of science, and his Periodic Law of Chemical Elements is one of the fundamental laws of natural science.

As a man of the most extensive intellect, possessing the most powerful mind, Mendeleev could work fruitfully in various branches of science. In addition to chemistry, Dmitry Ivanovich “noted” in physics and aeronautics, meteorology and agriculture, metrology and political economy. Despite not the easiest character and a very controversial manner of communication and defending his views, Mendeleev had an indisputable authority among scientists not only in Russia, but throughout the world.

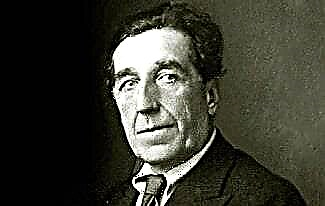

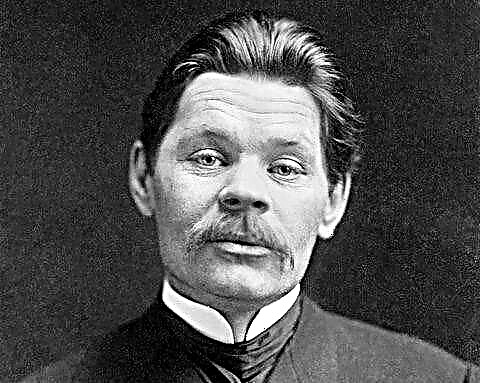

The list of scientific works and discoveries of D.I. Mendeleev is not difficult to find. But it is interesting to go beyond the framework of the famous gray-bearded long-haired portraits and try to understand what kind of person Dmitry Ivanovich was, how a person of such a scale could have appeared in Russian science, what impression he made and what influence Mendeleev had on those around him.

1. According to not the most well-known Russian tradition, of the sons of clergy who decided to follow in the footsteps of their father, only one kept the last name. D. I. Mendeleev's father studied at the seminary with three brothers. In the world they would have remained, according to their father, the Sokolovs. And so only the elder Timofey remained Sokolov. Ivan got the surname Mendeleev from the words “exchange” and “do” - apparently, he was strong in exchanges popular in Russia. The surname was no worse than others, no one protested, and Dmitry Ivanovich lived a decent life with her. And when he made a name for himself in science and became a famous scientist, his last name helped others. In 1880, a lady appeared to Mendeleev, who introduced herself as the wife of a landowner from the Tver province named Mendeleev. They refused to accept the sons of the Mendeleevs into the cadet corps. According to the morals of that time, the answer “for lack of vacancies” was considered almost an open demand for a bribe. The Tver Mendeleevs had no money, and then the desperate mother decided to hint that the leadership of the corps refused to accept Mendeleev's nephews into the ranks of the pupils. The boys were instantly enrolled in the corps, and the selfless mother rushed to Dmitry Ivanovich to report her misconduct. What other recognition for his “fake” surname could Mendeleev expect?

2. At the gymnasium, Dima Mendeleev studied neither shaky nor shaky. Biographers casually report that he did well in physics, history and mathematics, and the Law of God, languages and, above all, Latin, were hard labor for him. True, at the entrance exams to the Main Pedagogical Institute for Latin Mendeleev received a “four”, while his achievements in physics and mathematics were estimated at 3 and 3 “with plus” points, respectively. However, this was enough for admission.

3. There are legends about the customs of the Russian bureaucracy and hundreds of pages have been written. Mendeleev also got to know them. After graduation, he wrote a request to send him to Odessa. There, at the Richelieu Lyceum, Mendeleev wanted to prepare for the master's exam. The petition was fully satisfied, only the secretary confused the cities and sent the graduate not to Odessa, but to Simferopol. Dmitry Ivanovich threw such a scandal in the corresponding department of the Ministry of Education that the matter came to the attention of Minister A.S. Norov. He was not distinguished by an addiction to politeness, summoned both Mendeleev and the head of the department, and in appropriate expressions explained to his subordinates that they were wrong. Then Norkin forced the parties to reconcile. Alas, according to the laws of the time, even the minister could not cancel his own order, and Mendeleev went to Simferopol, although everyone recognized him as right.

4. The year 1856 was especially fruitful for Mendeleev's academic success. The 22-year-old took three oral and one written examinations for a master's degree in chemistry in May. For two summer months, Mendeleev wrote a dissertation, on September 9 he applied for its defense, and on October 21 he successfully passed the defense. For 9 months, yesterday's graduate of the Main Pedagogical Institute became assistant professor at the Department of Chemistry at St. Petersburg University.

5. In his personal life D. Mendeleev fluctuated with great amplitude between feelings and duty. During a trip to Germany in 1859-1861, he had an affair with the German actress Agnes Voigtmann. Voigtman did not leave any trace in the theatrical art, however, Mendeleev was far from Stanislavsky in recognizing a bad acting game and for 20 years paid a German woman support for his alleged daughter. In Russia, Mendeleev married the stepdaughter of the storyteller Pyotr Ershov, Feozva Leshcheva, and led a quiet life with his wife, who was 6 years older than him. Three children, an established position ... And here, like lightning strikes, first a connection with the nanny of his own daughter, then a short period of calm and falling in love with 16-year-old Anna Popova. Mendeleev was 42 then, but his age difference did not stop. He left his first wife and remarried.

6. Parting with the first wife and marriage to the second at Mendeleev took place in accordance with all the canons of the then non-existent women's novels. There was everything: betrayal, the unwillingness of the first wife to divorce, the threat of suicide, the flight of a new lover, the desire of the first wife to receive material compensation as large as possible, etc. And even when the divorce was received and approved by the church, it turned out that penance was imposed on Mendeleev for a period of 6 years - he could not marry again during this period. One of the eternal Russian troubles this time played a positive role. For a bribe of 10,000 rubles, a priest turned a blind eye to penance. Mendeleev and Anna Popova became husband and wife. The priest was solemnly defrocked, but the marriage was formally concluded according to all the canons.

7. Mendeleev wrote his excellent textbook "Organic Chemistry" solely for mercantile reasons. Returning from Europe, he was in need of money, and decided to receive the Demidov Prize, which was to be awarded for the best textbook of chemistry. The size of the prize - almost 1,500 silver rubles - amazed Mendeleev. Still, for a three times less amount, they, Alexander Borodin and Ivan Sechenov, had a glorious walk in Paris! Mendeleev wrote his textbook in two months and won the first prize.

8. Mendeleev did not invent 40% vodka! He really wrote in 1864, and in 1865 defended his thesis "On the combination of alcohol with water", but there is not a word about biochemical studies of different solutions of alcohol in water, and even more so about the effect of these solutions on humans. The dissertation is devoted to changes in the density of aqueous-alcoholic solutions depending on the concentration of alcohol. The minimum strength standard of 38%, which began to be rounded up to 40%, was approved by the highest decree in 1863, a year before the great Russian scientist began writing his dissertation. In 1895, Mendeleev was indirectly involved in the regulation of vodka production - he was a member of the government commission to streamline the production and sale of vodka. However, in this commission Mendeleev dealt exclusively with economic issues: taxes, excise taxes, etc. The title of “inventor of 40%” was conferred on Mendeleev by William Pokhlebkin. The talented culinary specialist and historian advised the Russian side in litigation with foreign manufacturers over the vodka brand. Either deliberately deceiving, or not fully analyzing the available information, Pokhlebkin argued that vodka had been driven in Russia since time immemorial, and Mendeleev personally invented the 40% standard. His statement does not correspond to reality.

9. Mendeleev was a very economic man, but without the stinginess often inherent in such people. He meticulously calculated and recorded first his own, and then family expenses. Affected by the mother's school, which independently ran the family household, contriving to maintain a decent lifestyle with very low incomes. Mendeleev felt the need for money only in his younger years. Later, he firmly stood on his feet, but the habit of controlling his own finances, keeping accounting books, remained even when he earned a gigantic 25,000 rubles a year with a university professor's salary of 1,200 rubles.

10. It cannot be said that Mendeleev attracted troubles to himself, but there were enough adventures found out of the blue in his life. For example, in 1887 he took to the sky in a hot air balloon to observe a solar eclipse. For those years, this operation was already trivial, and even the scientist himself perfectly knew the properties of gases and calculated the lift of balloons. But the eclipse of the Sun lasted two minutes, and Mendeleev flew in a balloon and then got back for five days, instilling considerable alarm in his loved ones.

11. In 1865 Mendeleev bought the Boblovo estate in the Tver province. This estate played a big role in the life of Mendeleev and his family. Dmitry Ivanovich managed the farm with a truly scientific, rational approach. How thoroughly he knew his estate is shown by a preserved unsent letter, apparently to a potential customer. It is clear from it that Mendeleev knows not only the area occupied by the forest, but is also aware of the age and potential value of its various sites. The scientist lists outbuildings (all new, covered with iron), a variety of agricultural implements, including the "American thresher", cattle and horses. Moreover, the St. Petersburg professor even mentions merchants who sell the products of the estate and places where it is more profitable to hire workers. Mendeleev was no stranger to accounting. He estimates the estate at 36,000 rubles, while for 20,000 he agrees to take a mortgage at 7% per annum.

12. Mendeleev was a real patriot. He defended the interests of Russia always and everywhere, making no distinction between the state and its citizens. Dmitry Ivanovich did not like the famous pharmacologist Alexander Pel. He, according to Mendeleev, was too admirable for Western authorities. However, when the German firm Schering stole from Pel the name of the drug Spermin, made from the extract of the seminal glands of animals, Mendeleev had only to threaten the Germans. They immediately changed the name of their synthetic drug.

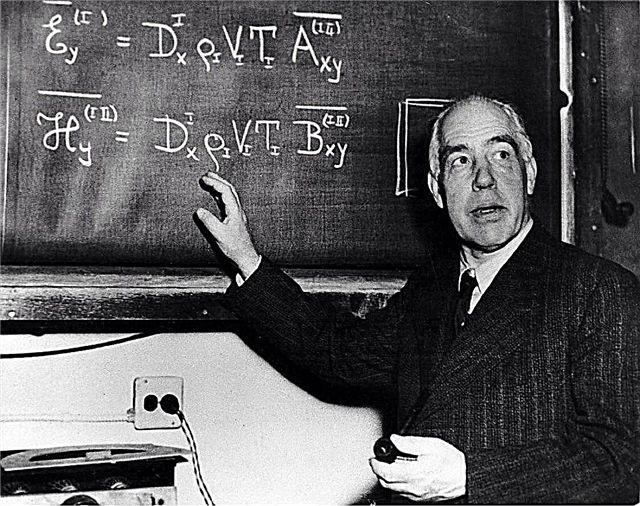

13. D. Mendeleev's periodic table of chemical elements was the fruit of his many years of studying the properties of chemical elements, and did not appear as a result of memorizing a dream. According to the memoirs of relatives of the scientist, on February 17, 1869, during breakfast, he suddenly became thoughtful and began to write something on the back of a letter that turned up under his arm (the letter from the secretary of the Free Economic Society, Hodnen, was honored). Then Dmitry Ivanovich pulled out several business cards from the drawer and began to write the names of chemical elements on them, along the way placing the cards in the form of a table. In the evening, on the basis of his reflections, the scientist wrote an article, which he passed on to his colleague Nikolai Menshutkin for reading the next day. So, in general, one of the greatest discoveries in the history of science was made on a daily basis. The significance of the Periodic Law was realized only after decades, when new elements “predicted” by the table were gradually discovered, or the properties of those already discovered were clarified.

14. In everyday life, Mendeleev was a very difficult person. Instant mood swings frightened even his family, to say nothing of the relatives who often stayed with the Mendeleevs. Even Ivan Dmitrievich, who adored his father, mentions in his memoirs how household members hid in the corners of a professor's apartment in St. Petersburg or a house in Boblov. At the same time, it was impossible to predict the mood of Dmitry Ivanovich, it depended on almost imperceptible things. Here he, after a complacent breakfast, getting ready for work, discovers that his shirt is ironed, from his point of view, badly. This is enough for an ugly scene to begin with a swearing at the maid and wife. The scene is accompanied by throwing all the available shirts into the corridor. It seems that at least assault is about to begin. But now five minutes have passed, and Dmitry Ivanovich is already asking forgiveness from his wife and the maid, peace and tranquility have been restored. Until the next scene.

15. In 1875, Mendeleev initiated the creation of a scientific commission to test the very popular mediums and other organizers of spiritualistic seances. The commission conducted experiments right in Dmitry Ivanovich's apartment. Of course, the commission could not find any evidence of the activities of otherworldly forces. Mendeleev, on the other hand, delivered a spontaneous (which he did not like very much) lecture at the Russian Technical Society. The commission completed its work in 1876, utterly defeating the "Spiritualists". To the surprise of Mendeleev and his colleagues, part of the “enlightened” public condemned the work of the commission. The commission even received letters from church ministers! The scientist himself believed that the commission should have worked at least in order to see how large the number of those who were mistaken and deceived could be.

16. Dmitry Ivanovich hated revolutions in the political structure of states. He rightly believed that any revolution not only stops or throws back the process of development of the productive forces of society. The revolution always, directly or indirectly, gathers its harvest among the best sons of the Fatherland. Two of his best students were potential revolutionaries Alexander Ulyanov and Nikolai Kibalchich. Both were hanged at different times for participating in attempts on the life of the emperor.

17. Dmitry Ivanovich very often went abroad. Part of his travels abroad, especially in his youth, is explained by his scientific curiosity. But much more often he had to leave Russia for representative purposes. Mendeleev was very eloquent, and even with minimal preparation, he delivered very flamboyant soulful speeches. In 1875, Mendeleev's eloquence turned an ordinary trip of a delegation from St. Petersburg University to Holland into a two-week carnival. The 400th anniversary of Leiden University was celebrated, and Dmitry Ivanovich congratulated his Dutch colleagues with such a speech that the Russian delegation was overwhelmed with invitations to gala dinners and holidays. At a reception with the king, Mendeleev was seated between the princes of the blood. According to the scientist himself, everything in Holland was very good, only “the Ustatok won”.

18. Almost one remark made at a lecture at the university made Mendeleev an anti-Semite. In 1881, student riots were provoked at the Act - a kind of annual public report - of St. Petersburg University. Several hundred students, organized by classmates P. Podbelsky and L. Kogan-Bernstein, persecuted the university leadership, and one of the students hit the then Minister of Public Education A. A. Saburov. Mendeleev was outraged not even by the fact of insulting the minister, but by the fact that even students who were neutral or loyal to the authorities approved of the vile act. The next day, at a planned lecture, Dmitry Ivanovich moved away from the topic and read a short suggestion to the students, which he finished with the words “Kogans are not kohans for us” (Little Russian. “Not loved”). The progressive strata of the public boiled and roared, Mendeleev was forced to leave the course of lectures.

19. After leaving the university, Mendeleev took up the development and production of smokeless powder.I took it, as always, thoroughly and responsibly. He traveled to Europe - with his authority there was no need to spy, everyone showed everything themselves. The conclusions drawn after the trip were unambiguous - you need to come up with your own gunpowder. Together with his colleagues, Mendeleev not only developed a recipe and technology for the production of pyrocollodion gunpowder, but also began to design a special plant. However, the military in committees and commissions easily blabbed even the initiative that came from Mendeleev himself. No one said that gunpowder is bad, no one refuted Mendeleev's statements. It's just that somehow like this all the time it turned out that something was not yet time, that is, more important than care. As a result, the samples and technology were stolen by an American spy who immediately patented them. It was in 1895, and even 20 years later, during the First World War, Russia bought smokeless powder from the United States with American loans. But gentlemen, the artillerymen did not allow the civilian spar to teach them the production of gunpowder.

20. It has been reliably established that there are no living descendants of Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev left in Russia. The last of them, the grandson of his last daughter Maria, born in 1886, died not so long ago from the eternal misfortune of Russian men. Perhaps the descendants of the great scientist live in Japan. Mendeleev's son from his first marriage, Vladimir, a naval sailor, had a legal wife in Japan, according to Japanese law. Foreign sailors then could temporarily, for the period of the ship's stay in the port, marry Japanese women. The temporary wife of Vladimir Mendeleev was called Taka Khidesima. She gave birth to a daughter, and Dmitry Ivanovich regularly sent money to Japan to support her granddaughter. There is no reliable information about the further fate of Tako and her daughter Ofuji.